Kate Fielding is the departing head of strategic communications at the Natural History Museum, with overall responsibility for the museum’s reputation and brand. Heading up three teams – media and PR, Government relations, and special events and supporter engagement – Kate works on integrated comms and strategic messaging.

Since Kate joined, she’s been steering the Natural History Museum through a comprehensive brand extension in order to shift both public and stakeholder perceptions from just a cultural tourist attraction to an authoritative scientific institution.

We spoke to Kate about the challenges she’s faced along the way and how a museum of natural history is the key to saving our natural future.

What are the Natural History Museum’s aims?

Our purpose statement is: Inspiring love of nature and finding answers to the big issues facing humanity and the planet.

Saving the world?

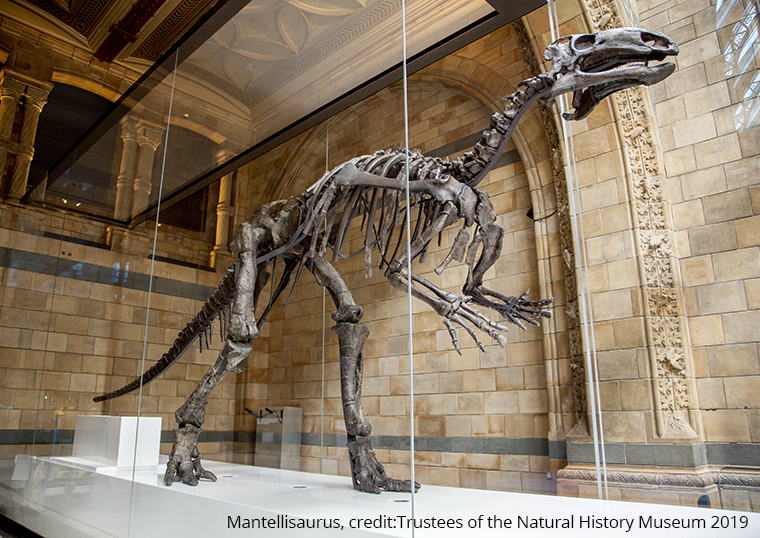

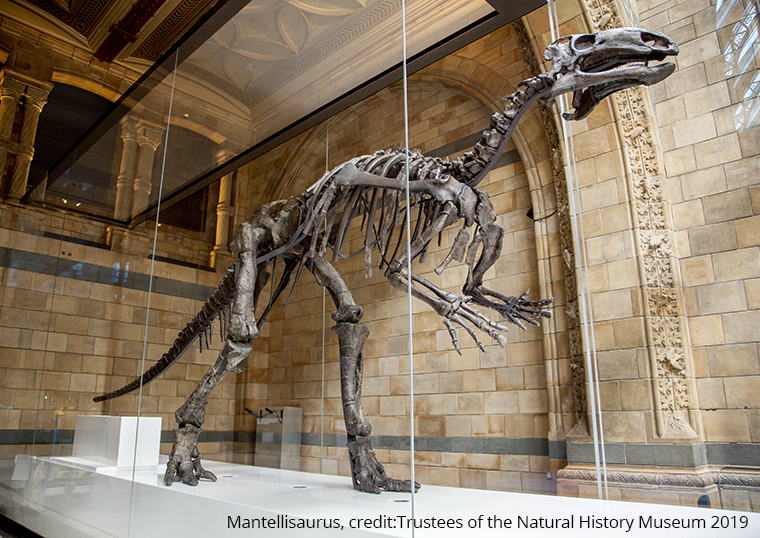

Helping to save the world. It’s a big ambition and it’s about changing the way the museum is seen from a lovely old dusty building full of dead stuff to a scientific organisation, which provides a platform for engaging people with important debates. We want to help the country find the right solutions if we’re to have a future where people and the planet thrive together, which is very much in peril at the moment.

The Natural History Museum and other museums around the world have a very important role to play because our collections are not just cultural but they’re actually a scientific record that goes back, in some cases, four and a half billion years, and span the entire planet. You can look at what’s happened over time and space and see what happens if the climate changes or land is used in specific ways.

It’s something that people generally don’t know about this kind of museum, what we do and why it’s important.

How does communications work across the museum?

Museums are complex businesses. There’s effectively a small university bolted on the back of the public galleries, which has 350 scientists working on research projects and curating collections. Then there’s the bit most people think of as ‘the museum’ which is public facing and needs us to develop public programmes, exhibitions and events, as well as look after the visitors. Alongside that are our commercial businesses, which are growing in importance. Catering, retail, licensing and venue hire are all income streams.

We then have the philanthropic income development, working with trusts, foundations and high net worth individuals for funding. And then all the support structures that go into a medium-sized organisation.

Often, because it’s so complex, the way to manage it has been to work in siloes. For comms, that risks there being no coherent or consistent message and making it difficult to get across those big, exciting messages about what we’re aiming to achieve and why people should want to be a part of that. What I’ve been doing is finding ways to bring that story together within a thematic and strategic framework that’s consistent across the Museum.

Is your message the same for everyone?

The agenda and perceptions of a family coming for a fun day out and a Government minister visiting in an official capacity is hopefully different, so we have a range of messaging. What we’ve tried to do is put the brand at the heart of what we’re doing, the idea of inspiration and action whether that’s through science or otherwise.

I think in the past a lot of people haven’t seen us as a very fun day out, but as an educational destination. We did market research into this and even though we’re free to visit, if you’re coming from outside of London you’re looking at the cost to travel in, buy food and probably one or two things from the gift shop. With austerity hitting families, people are making judgements about whether they’re going to have a really great day out for that investment.

For those people, we need to say we’re a fun place to come, which is why we did the Come to Life campaign with outdoor advertising, having fun with specimens and exhibits in playful poses and accompanying ‘speech’. It also played really well on digital and social.

Down the other end we’ve got Government, who are funders, and philanthropic and corporate funders. For them, it’s about showing the work we’re doing and our ability to make an impact, whether that’s climate change and having food to eat in the future, or children in education and STEM subjects.

This work is based around a visit and events programme, because the museum is an incredible asset. We primarily try to get people in and show them everything on public display and behind the scenes, in the Tank Room, for example.

How do you measure the success of this work?

We’ve just completed a big piece of perceptions research as a baseline for public and stakeholder audience groups. It looks at where are we now, what do they think of us and what do they understand of our remit and key messaging? We’ll then measure that again, probably not annually but every couple of years to see if it’s all going in the right direction.

In the short term, we measure the success of individual campaigns. So, for any of the big exhibitions we’ll do a joint comms and marketing report and how well it’s performed with message cut through. It’s not just the profile and the reach but finding out if we landed the fundamental messages that we wanted to get across with that.

With digital and social now in the mix, you’ve got bits of the picture that are easier to measure, and the commercial parts of the business are easier to prove and link together online. Obviously that’s attractive to people who want to see hard numbers and measure things in a certain way, but that can make it even harder to get across the value of things that are difficult to measure. For example, someone may not have taken immediate action seeing one of our scientists on the News at Ten but we know that’s important, it reminds people that we’re here and it has an impact on visitation but we can’t prove that unless we interrogated everyone as they came through the door.

It sounds like there’s lots of considerations when proving ROI?

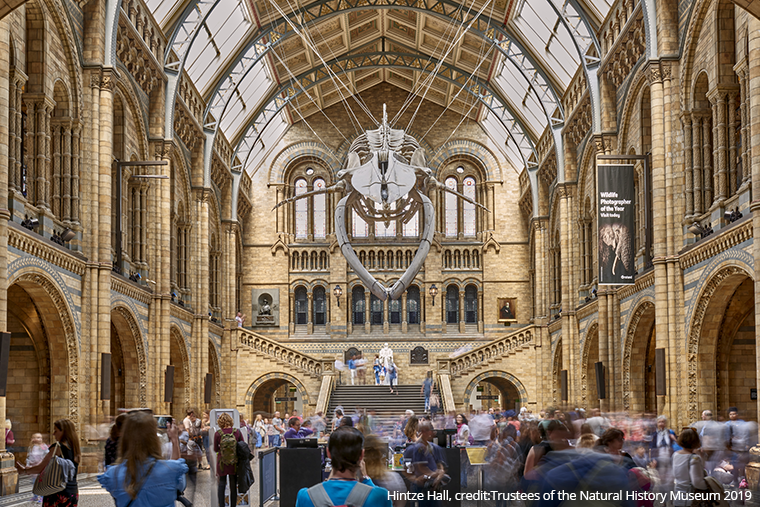

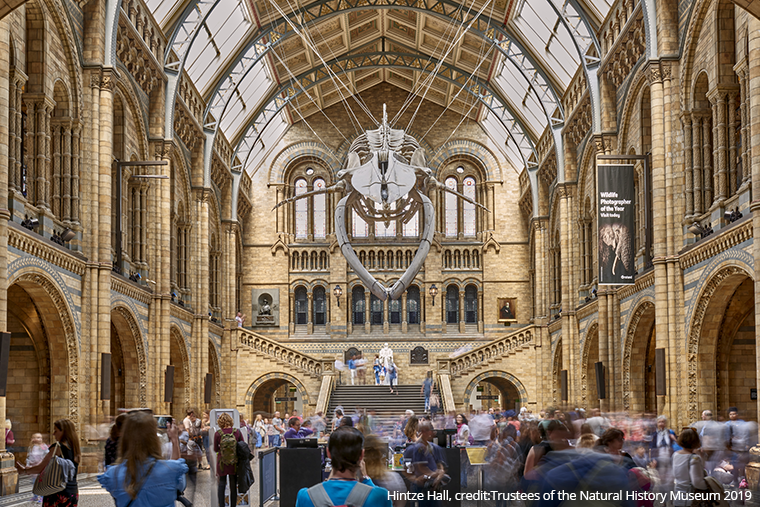

Just after a year after I started, we relaunched Hintze Hall with our iconic whale skeleton and hundreds of new exhibits in a spectacular transformed space – it was incredible. We got amazing results in terms of the profile and messaging around that, the media team did a brilliant job, but we can’t put that success or an increase in visitors just down to the media team because people have been working for years to bring the project to life.

On the other hand, sometimes you can see direct cause and effect – we had a Darwin play at the museum and our director of engagement went on BBC Breakfast to talk about it and we could see the ticket sales spike dramatically.

A typical consideration in comms is the competition and here you’re surrounded by other museums. Do you see them as competition?

I’m sure in some ways we’re competing with each other, but we work really closely with the museums and cultural institutions in the area. We recently had the Great Exhibition Road Festival, which brought together 22 institutions in Kensington to mark the anniversary of the Great Exhibition of 1851. We’re in a cultural quarter and there’s a lot of great collaboration between the museums, particularly in attracting international visitors to get them to the area.

Museums in general aren’t competitive in the way other commercial businesses are – there’s a feeling we’re part of a national culture. All the national museums are funded by DCMS and there’s an expectation we work together for the public benefit and across the UK.

But obviously when the annual visitor numbers come out, we want to be near the top…

Social media is a potential source of stress for your clients, yet it’s a vital way for them to cut through and achieve success in today’s media landscape. How can it be used as a tool without it becoming a strain for clients and the companies working with them?

Social media is a potential source of stress for your clients, yet it’s a vital way for them to cut through and achieve success in today’s media landscape. How can it be used as a tool without it becoming a strain for clients and the companies working with them?